About a year ago, it seemed like something was wrong with Baxter.

Our usual low-energy dog became lethargic.

We went through lots of tests, tried different medications, consulted several specialists, confronted various symptoms and never received a definitive diagnosis.

As I shared in my last post, Baxter died at the end of May. In the last weeks of his life, he developed what our vets called intra-cranial disease. It manifested as a form of dog dementia or canine cognitive dysfunction (CCD). I am sharing an introduction to CCD along with our year-long journey today.

What is Canine Cognitive Dysfunction? (Dog Dementia)

Canine cognitive dysfunction, or dog dementia, is a neurological condition that affects some dogs as they age. Abnormalities develop in their brains and lead to behaviour changes.

Eileen Anderson is an author and dog owner. In her guide to CCD, she provides a detailed list of symptoms.

Symptoms of dog dementia

- Disorientation

- Interactions with people and other pets that have changed

- Sleep-wake alterations

- House soiling

- Activity-level alterations

- Memory and learning problems

- Appetite changes

- Anxiety and depression

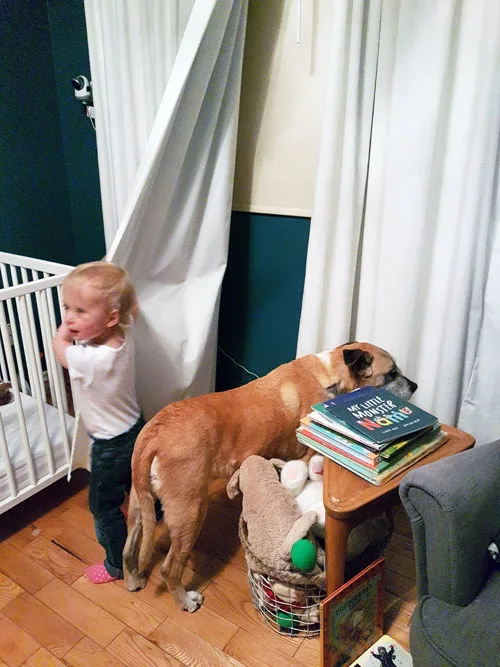

For Baxter, lethargy was the first symptom we observed. As his illness progressed, he needed to go outside for bathroom breaks more frequently. He became weak and had trouble going from lying to standing on his own.

We also experienced appetite changes. He lost interest in his kibble, so we switched to a raw diet. He loved it… for a few months. Eventually, he lost the ability to eat on his own, and I fed him by hand for several months. In the last weeks, he did not know how to eat or drink, and I fed him by syringe.

Disorientation

Disorientation is a common CCD symptom that we also experienced. An article on The Bark says, “Dogs may pace back and forth or in circles [I had noticed Baxter turning and turning multiple times before laying down—a new behaviour for him—for several months before he died], get lost in familiar places, walk into walls or corners or other tight spaces and stay there, appear lost or confused, wait at the “hinge” side of the door to go out, or fail to get out of the way when someone opens a door.”

We experienced all of these. I spent a lot of time gently pulling and pushing Baxter out of corners and guiding him back to his bed or through the door.

Difficult to diagnose

CCD can be difficult to diagnose. Anderson notes, “Every symptom on those lists could also be a symptom of another disease or condition. Brain tumors, certain liver conditions, tickborne diseases, and other conditions can cause similar symptoms. Diagnosing canine cognitive dysfunction means ruling those other things out. It’s called a diagnosis of exclusion, and it takes a vet to do the appropriate tests to do that.”

Like dementia in humans, there is no cure for dog dementia. But there are ways to manage CCD once your dog is diagnosed.

Drugs and foods can help to slow progression of the disease or manage symptoms for some dogs. As well, lifestyle changes will be necessary, like finding ways to keep your dog active, providing him with enrichment to stimulate his brain and making your house a safe environment.

Ultimately, pet owners will likely be faced with euthanizing their dog, as his quality of life deteriorates and his bodily functions become more and more impaired by this disease.

Below, I share our experience with dog dementia, from the onset of Baxter’s symptoms to his death a year later.

Something Is Not Right

Baxter started acting not like himself in the late spring of 2019. Never energetic, he became lethargic. He didn’t want to go on walks or even walk around inside the house very much. He just lay in his bed and slept.

Baxter seemed to be drinking a bit more, peeing a bit more and always hungry.

When we went to the vet, their first suspicion was Cushing’s disease. They took blood and urine samples and found his urine was extremely diluted. We did more tests, including those commonly used to detect Cushing’s. Some of Bax’s results matched, but others didn’t.

After putting Bax through many vet visits over the summer and spending a fair amount of money, we had not found a solution. Since Bax didn’t seem to be in pain or other distress, we decided to take a break and accept the lethargy.

We switched from kibble to a raw diet, which he liked, but didn’t improve his energy. As noted above, diet is one of the few options to manage symptoms and slow progression of CCD.

It’s Still Not Right

We returned to the vet in March 2020. Baxter seemed to be even more lethargic, and he had started asking to go outside for the bathroom in the middle of the night. He also seemed to have developed a pot belly, one of the symptoms of Cushing’s.

When he stepped on the scale, I was blown away. Our usual 60 pound dog weighted 82 pounds. We had not been over-feeding him, and he didn’t look fat. The vet tech described him as “puffy” around his neck and on his belly. One of my guesses is that his lack of activity had resulted in weight gain.

Maybe it’s Cushing’s disease

The vet ran the same tests as before and the results were the same as before—inconclusive. They also took an x-ray, which showed Bax’s joints, particularly his hips, were in bad shape. But that didn’t answer the rest of what was going on.

Our vet decided to try a very low dose of Vetoryl, a common Cushing’s medication. Vetoryl can have some very serious side effects, so we were very cautious.

We didn’t see an improvement. In fact, on the medication, Baxter stopped eating. Eventually, he developed diarrhea (one of the symptoms our vet told us to watch out for), so we stopped the Vetoryl.

Maybe it’s his thyroid

Our vet suggested trying a thyroid medication.

Again, we didn’t see an improvement, and Baxter’s appetite continued to decline.

I started to hand feed him. I could get him to eat the amount of food he was supposed to but it took all day and into the evening for him to eat it all. Baxter was able to drink on his own and needed to go out to pee quite frequently including through the night.

He weakened, whether from not eating or from lack of activity. He had trouble standing up, and we laid mats around the house to help him get traction on the wood floors.

By now, it was mid-April and we were in a COVID-19 quarantine. Our vet wanted to refer us for an ultrasound and for a consult with another specialist. We live near one of the top veterinary colleges in Canada, but they, like most vet clinics, were only dealing with emergencies. Our options were very limited.

After waiting several weeks, our vet found a specialty clinic in Toronto—more than an hour away—that would see us.

More tests and an ultrasound

I really wanted an ultrasound. Having gone through liver metastases with my husband, Matt, just a few months ago, all I could think was that Baxter had tumours in his liver and that was why his belly was bulging.

An ultrasound was part of our appointment at the speciality hospital. And everything was clear. Good news in some ways. But bad news because we still had no answer. The internal medicine specialist explained that sometimes the belly can become distended just because the muscles are not as strong as they once were. Given Bax’s lack of activity, this made sense and gave me some reassurance that his pot belly wasn’t a symptom of some terrible condition.

The ultrasound showed that his adrenal gland was slightly enlarged, but, like our family vet, the specialists were not sold on Cushing’s. They also redid all of the blood work and did a urine culture to check for a urinary tract infection. His bloodwork showed that one of his liver enzymes was slightly elevated. The urine culture showed no bacteria.

We had more information, but still had no answer.

Psychological Considerations

In my briefing to the specialist, I raised the possibility that Baxter’s condition might be psychological.

Matt had died in November. The onset of Baxter’s symptoms, in many ways, coincided with Matt’s own decline. Dogs are sensitive creatures, and Baxter had shadowed Matt a lot over his last months.

After Matt died, there then was a huge hole in our family and immense sadness in our house.

I felt that psychology likely didn’t explain all of Baxter’s symptoms, but I wanted it to be considered as the doctors assessed him.

Complications

The appointment at the specialty clinic was hard. Given COVID-19, I couldn’t go in with Bax. He doesn’t like the vet, and I feel like being with him helped him get through the appointments. And the appointment ended up being much longer than I expected. I had brought work and snacks and planned to sit in the car while he was in the clinic.

But they wanted to do additional tests, and they had to sedate him for the ultrasound, so they needed to monitor him once he woke up. I drove home and made arrangements to pick him up later. Later ended up being much later—well into the evening.

The clinic staff had trouble getting him to wake up from the sedation, so they kept him for observation and hoped he’d come out of it. Eventually, they gave me the option to bring him home and let him sleep it off here.

When I arrived at the clinic I was stunned. It took two techs to walk him out to the car. They had a towel slung under his belly to support him. He was so groggy and disoriented he couldn’t walk. And the ultrasound had been hours ago.

I got him home and into the house. He slept, though he whimpered pretty consistently for about two days straight.

Bax’s crying had started at the clinic, leading the staff to think his joints were bothering him more than I realized. They gave us some Gabapentin for pain relief.

Neurological Symptoms Become Obvious

After a few days, Baxter eventually stopped whimpering and regained the ability to walk—though I did not give him the Gabapentin. We had new symptoms that were more concerning. It seemed like he had dog dementia.

He was very disoriented and got lost in the house. He walked right up to the wall, into corners or dead ends (beside the toilet for example) and then stood there for several minutes. I needed to guide him through the house and sometimes physically lay him down on his bed.

He stopped eating and mostly stopped drinking. It seemed like he did not know what to do with his mouth. He knew enough to go to his water bowl, but then he just stood there. When he did try to drink, it appeared like he was trying to chew the water rather than lap it.

I was able to feed him by syringe. Our vet gave us some Cernia to try to stimulate his appetite, but he had no idea how to take food from a bowl or even from my hand.

Between his test results and new behaviours, our family vet as well as the specialist suspected there was something neurological going on.

The specialty hospital included a neurological team, and they recommended we make another appointment. However, given Bax’s reaction to the appointment and/or medication, I did not want to put him through another appointment.

Our family vet agreed. We had a long, compassionate, realistic conversation about possible diagnoses and treatment options, and he advised that our options were likely few.

Helping Baxter

I planned to keep feeding Bax and helping him however I could. The next two weeks were challenging.

Baxter spent most of his time lying down. When he did get up, he was confused and lost.

I diluted his food as much as possible to try to keep him hydrated. He took the syringe without protest and was able to go outside for the bathroom. I blocked off the stairs to the basement so that he didn’t fall.

I was constantly listening for him, checking on him and monitoring him. Did he need help getting up? Did he need to go outside? Could I get him to eat a bit more food? Was he stuck somewhere? Could I guide him back to bed and get him to lay down again?

One day he followed me down to our pond. I was happy that he felt up to walking a bit more. But when we got to the shore, he just kept walking. Right into the water. Baxter has never swam in the whole time he lived with us. As I prepared to jump into the water to help him, I discovered he could in fact swim. I was able to coax him back to shore and up to the house where I towelled him off and guided him inside and back to his bed.

Reaching The End

Toward the end of May, I finally felt that Bax was not getting any enjoyment or fulfillment out of his days. He was not engaging with us or his surroundings. I felt that he didn’t recognize me anymore.

I called the vet and made an appointment for him to be put down.

Despite still being mostly under quarantine, I feel very grateful that the vet was willing to come to our farm, and I was able to bring Baxter outside and he was euthanized here at home.

In the end, we never received a definitive diagnosis. Perhaps he had a brain tumour. Perhaps he had CCD. In the research I have done, it seems like dementia is an explanation for Bax’s symptoms going back over the last year.

Neurological conditions and Canine Cognitive Dysfunction are challenging diseases. In these, as in everything with our pets, we do our best and work to live fulfilling, happy, loving lives with our dogs.

Julia Preston writes for That Mutt about dog behavior and training, working dogs and life on her farm in Ontario, Canada. She has a sweet, laid-back boxer mix named Baxter. She is also a blogger at Home on 129 Acres where she writes about her adventures of country living and DIY renovating.

Related posts:

Nancy Stordahl

Wednesday 9th of September 2020

Hi Julia, Thank you for writing about your experience trying to help Baxter. CCD is something we're dealing with right now with our Sophie. She has many of the classic signs. Even though she's 14+ and CCD isn't really unexpected at her age, it's still so hard and sad to watch your beloved pet struggle. I like what you suggested to Dawn about trying not to focus on the decline, but rather to enjoy what you still can together. That's what we're trying to do and will keep trying to do for as long as possible.

I'm sorry you've experienced the heartbreaking loss of Matt and then so soon after, Baxter too. Thank you for sharing about both experiences. I hope writing about them helps just a bit.

Stacey Kline

Wednesday 29th of July 2020

Oh, Julia, I am so sorry for your two losses in a short time. But your testimony of loving and caring for Bax is beautiful. He was lucky to have you. (My guess is that you cared for your husband in a similar way).

Julia P.

Thursday 30th of July 2020

Thank you for your kindness, Stacey. We all do lots of things for those we love.

Dawn

Wednesday 29th of July 2020

I just cried my eyes out. This story is so sad. It's always depressing seeing a pet decline, and so soon after your husband's death. I can't even imagine how hard that was for you. *hugs*

You mentioned The Bark's article, "...appear lost or confused, wait at the “hinge” side of the door to go out, or fail to get out of the way when someone opens a door." This caught my attention because Maya has been doing this. She's almost thirteen years old, so cognitive deterioration shouldn't be surprising. But it makes me sad to see her decline. She's been through a lot of life changes with me and I don't know what I'll do without her.

Julia P.

Thursday 30th of July 2020

I second Lindsay's comment. Work with your vet if you're particularly concerned about Maya, but try not to fixate on her decline. Enjoy as much as you can together. I have learned that even in the hardest, darkest times, there is always good, and focusing on that can help everyone.

Lindsay Stordahl

Wednesday 29th of July 2020

Hi Dawn, my senior dog Ace (RIP) would also wait at the "hinge" side and he had a few other mild symptoms of dementia. I'm sure, like people, some dogs show only mild symptoms and some show more. It's nice to hear about sweet Maya. I hope she is doing well overall.